Too Big To Fail

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

🌻 Happy first day of spring, everybody.

Stocks rose Monday as bank concerns eased, at least for now, ahead of the Federal Reserve’s meeting this week. Most expect a quarter-percentage-point interest rate increase this week.

But it’s one of the Fed’s toughest calls in years: raise interest rates again to fight inflation or take a foot off the gas amid the most intense banking crisis since 2008.

Meanwhile, in technology, Amazon will lay off 9,000 additional employees in the coming weeks, CEO Andy Jassy said in a memo to staff Monday, marking the second-largest round of layoffs in the company’s history.

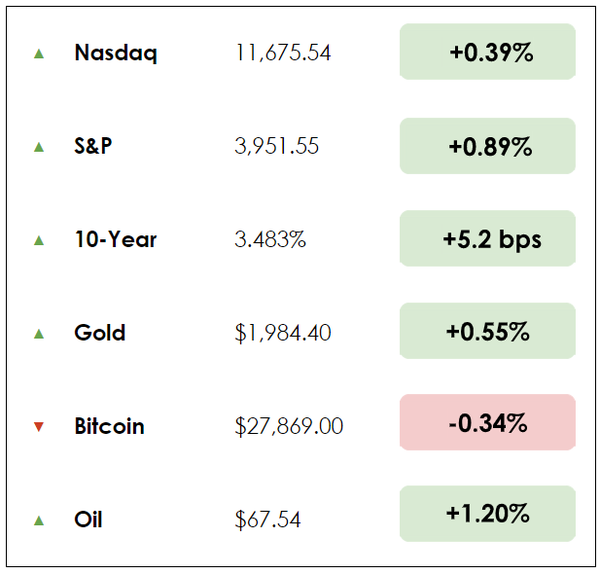

Here’s the market rundown:

MARKETS

*All prices as of market close at 4pm EST

Today, we’ll discuss two items in the news:

- Why UBS bought Credit Suisse and what it means

- A bond wipeout threatens a $250 billion market

- Plus, our main story on Jim Simons and his remarkable run

All this, and more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Get smarter about valuing businesses in just a few minutes each week.

Get the weekly email that makes understanding intrinsic value

easy and enjoyable, for free.

Real estate investing, made simple.

17% historical returns*

Minimums as low as $5k.

EquityMultiple helps investors easily diversify beyond stocks and bonds, and build wealth through streamlined CRE investing.

*Past performance doesn’t guarantee future results. Visit equitymultiple.com for full disclosures

IN THE NEWS

⏳ UBS Buys Credit Suisse (Bloomberg)

Explained:

- With the stability of global markets on the line, UBS, Credit Suisse, and Swiss regulators reached a last-minute deal on Sunday that valued Credit Suisse at just 0.76 francs per share, a 99% fall from its peak price. It’s a stunning collapse for the 166-year-old banking institution that’s one of 30 with a globally systemic banking (GSIB) designation — it was too big to fail, and regulators didn’t let it.

- The affair will make for a great script in future movies documenting the storied bank’s implosion in a country with a defining banking tradition. The deal, brokered by the Swiss government, has UBS purchasing its chief rival at $3.2 billion, a considerable discount to Credit Suisse’s $8 billion market capitalization, as late as Friday.

- To sweeten the deal for a hesitant UBS, not excited about absorbing the scandal-plagued bank’s fast-deteriorating reputation and money-losing investment banking business, the Swiss National Bank is offering 100 billion francs in liquidity assistance (funds to borrow as needed) while providing a nine-billion franc guarantee for potential loses on the assets that UBS is taking over. On top of this, 16 billion francs worth of Credit Suisse bonds, known as AT1s, will become worthless — more on that later.

- The Federal Reserve welcomed the deal, hoping it might finally stabilize markets. It announced on Sunday a plan, alongside five other central banks, to take coordinated action to boost liquidity globally via U.S. dollar swap line arrangements.

Why it matters:

- Governments worldwide are hurrying to stem a banking panic before it consumes more of the financial system. For Credit Suisse, which was reportedly losing $10 billion per day in deposits, Swiss regulators had to push for an emergency marriage of convenience with its peer Swiss banking giant.

- Unlike 2008, this wasn’t necessarily a banking collapse caused by risky lending practices and hard-to-value assets. Rather, it was a crisis of confidence for a scandal-ridden organization. One portfolio manager commented, “In this case, a bank could fail although there was no major loss on the balance sheet — this is a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. If everyone believes it will fail, it fails.”

- And UBS made it clear that it plans to make some changes. Its chairman remarked, “Let me be very specific on this: UBS intends to downsize Credit Suisse’s investment banking business and align it with our conservative risk culture.”

- For the Swiss government, the crisis has proven existential, with one official saying, “If we as a country, where finance makes such a large part of GDP, are not able to send out a signal that ‘we can stop this’ — then we can close down. Nobody in the world will believe us anymore.”

👀 Bond Wipeout Threatens $250 Billion Market (WSJ)

Explained:

- As mentioned above, for an acquisition of Credit Suisse to make sense for UBS, around $17 billion of what’s referred to as additional tier 1 bonds (AT1s) needed to be wiped out. These bonds, also called contingent convertible bonds, or CoCos, were introduced after the 2008 financial crisis to transfer banking risk away from taxpayers and onto bondholders. At Credit Suisse, they were popular investment products to sell that could seemingly boost returns on bond portfolios at low risk.

- Many European banks issued AT1 bonds despite their higher interest rates because their “bail-in” features reassured regulators they had enough capital buffer to protect against a crisis. And in a crisis, these bonds could convert to equity when triggers were reached, such as capital ratios falling below a certain level or if regulators had to intervene on a bank’s behalf.

- But Swiss officials had to make an unconventional decision: Wiping out bondholders before shareholders. Finance 101 tells us that bondholders, the lenders of capital to a business, should sit above shareholders, the owners of a business, in a company’s capital structure. Meaning, lenders should get paid back first, while shareholders, who stand to gain more in good times, should lose the most in bad times.

- Unlike other European banks, Credit Suisse’s AT1s included a provision where these bondholders could lose their entire investment before shareholders do. Now, AT1 holders will get nothing, while shareholders will receive UBS stock in exchange for their shares in Credit Suisse.

Why it matters:

- Around $254 billion in AT1 bonds are outstanding, and the market for these securities is reeling. Deutsche Bank saw its AT1 bonds fall 10% last week, even before the Credit Suisse deal on Sunday, while UBS’s own AT1s fell 5%. Most of these bonds are held by insurers and pension funds or sold to individual investors outside of Europe through investment funds.

- Ironically, a 2021 report from Credit Suisse suggested these bonds were very safe because: “The average European bank would need to lose almost two-thirds of its capital to breach contractual triggers. In our view, this is a relatively remote scenario.” Remote as it may be, here we are.

- The complete write-off of Credit Suisse’s bonds, from one of the largest issuers of AT1s, will likely weaken investors’ appetite for these types of securities going forward. That would make the bonds more expensive for banks to issue, reducing their ability to make new loans.

WHAT ELSE WE’RE INTO

📺 WATCH: How Silicon Valley broke productivity

👂 LISTEN: Defensive investing in dangerous times with Guy Spier

📖 READ: Returns & how they get the way by Howard Marks

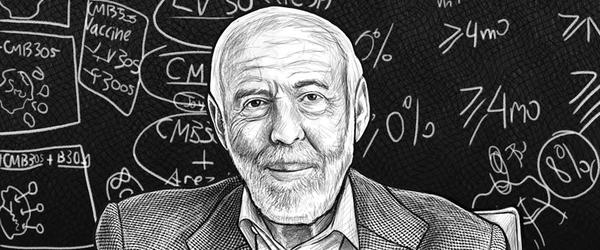

As stocks fell in late 2018, Jim Simons was on vacation with his wife in California. He was already a billionaire many times over, but seeing red on his screen played with his emotions. He called his money manager.

“Shouldn’t we be protecting here, shouldn’t we be shorting?”

Ultimately, his manager urged him to resist the temptation to act. They did nothing, the market bottomed the next day, and their portfolio soared in value throughout 2019.

Though Simons felt the stress of a market drawdown, his life’s work has been about removing emotions from investing through quantitative trading. Theoretically, it’s all numbers and computers, with zero human bias.

His team returned 66% annually, before fees, for more than 30 years, a track record that might not be replicated.

By that measure, his hedge fund, Renaissance Technologies, is the greatest of all time.

Origins

It’s a fascinating rise for Simons, who grew up outside of Boston, became a math genius, worked as a code-cracker for the U.S. government, and only dabbled in the stock market. By 30, he led a university math department, and by 44, he had founded one of the world’s most successful hedge funds.

In 1982, he launched his quantitative-focused fund Renaissance Technologies from a strip mall in Long Island.

Simons, now 84, is a renowned mathematician and investor known as the “Quant King.” He’s now worth around $30 billion.

Gregory Zuckerman’s book, “The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution,” notes that Simons respects fundamental analysis but doesn’t want to get caught up in stories. By deferring to models and the scientific method, he’s less likely to fall for behavioral bias.

Simons summed up his investing approach in a 2016 interview when he said he has no opinions on stocks. “The computer has its opinions, and we slavishly follow them,” he said.

Renaissance’s methods are proprietary and secret — but he has said he “never overrode the model.” Once he settled on what should happen, he held tight until it did. In other words, he didn’t overthink many decisions or second-guess, valuable traits for any investing approach.

In other words, Simons offers a masterclass in discipline – all systems have losing streaks and drawdowns, and sticking with a model when it isn’t working is one of his best qualities.

Best player

His firm is somewhat of an anomaly also; they don’t employ business or finance graduates but do employ scientists, programmers, physicists, cryptographers, computational linguists, and mathematicians. Simons spent plenty of time recruiting talent, looking for the best “player” available, rather than who can fill a specific role. Here’s Simons:

‘The model has been, first hire the smartest people you can. Work collaboratively. Let everyone know what everyone else is doing. We have one system, and once a week, there is a research meeting. If someone has something new, it gets presented. It gets chewed up and looked at. The code is there, everyone can look at the code and see what they think, does this really work? It is a very collaborative enterprise and I think that’s the best way to accelerate science.”

His hedge fund specializes in diversified system trading using individual quantitative models derived from statistical analyses of historical price data. His primary models are based on pattern recognition, but there are very few details about Renaissance’s process. (Hedge funds are notoriously private.)

In the 31 years from 1988 through 2018, the Medallion Fund — the flagship of Simons’s Renaissance Technologies — achieved a breathtaking 69% gross return (39% after fees that eventually rose to a staggering 5-and-44) by grossly violating weak-form market efficiency; price and volume movements do affect future prices.

Simons paved the way for a quant revolution.

Other lessons & key quotes

Interestingly, Simons isn’t necessarily a fierce backer of the strategy that has made him rich.

“(Fundamental investing) is a perfectly legitimate way to invest. Look at Warren Buffett, I don’t think he has a computer on the premises, except maybe to count his money.”

“I think there is a world of difference between being a good fundamental investor and a good quant. A good fundamental investor wants to evaluate the management, have a sense of the human beings running it, a sense of where the market might be going. It’s a set of skills. And some people are very good at it. Quantitative stuff is a different set of skills.” Simons knows how much luck has helped him and his team, noting that, “Luck plays quite a role in life; we’ve been lucky.”

He also advocates for being hands-off and letting space for the mind to wander, away from models and spreadsheets.

“I like to ponder. And pondering things, just sort of thinking about it and thinking about it, turns out to be a pretty good approach,” he has said.

What’s also fascinating: He was right hardly more than half the time. “We’re right 50.75 percent of the time… but we’re 100 percent right 50.75 percent of the time. You can make billions that way.”

SEE YOU NEXT TIME!

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.