Things are weird right now

6 July 2022

It’s Hump Day, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

Welcome back to We Study Markets.

Even though it’s a short week, the days after a long weekend are never easy. Thankfully, we’re here to provide some inspiration to power through.

Today we’ll be discussing Buffett’s latest investments, so-called ‘hyper-financialization’, why the economy is so weird right now, and much more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Let’s do it!

In The News

💰 Warren Buffett’s Berkshire raises stake to 16.4% in Occidental Petroleum (Reuters)

Explained:

- As Buffett frequently says, “be greedy when others are fearful, and fearful when others are greedy.” With market averages declining significantly this year, Buffett is living up to his own words. While some were critical of Buffett for not capitalizing on the fear in markets in March 2020 more, it appears he’s not letting this chance slip by. Buffett has actually been on a bit of a shopping spree lately, despite telling shareholders earlier this year that good deals were becoming hard to find, as he puts Berkshire’s treasure trove of cash ($147 billion in the first quarter of this year) to work. Some other notable Buffett investments this year include an $11.6 billion takeover of the Alleghany insurance conglomerate, Hewlett Packard, Activision Blizzard, Ally Financial, Citigroup, Paramount, Chevron, and more, totaling over $50 billion.

What to do:

- Many investors love to track The Sage of Omaha’s market activities, and after a relatively quiet period, he has undoubtedly jumped back to action despite being 91 years old. Buffett has a tremendous track record for buying-and-holding great companies, so there’s no shame in looking to his picks for your own inspiration. There’s also no shame in just owning Berkshire stock either 😉

🤔 If the U.S. is in a recession, it’s a very strange one (WSJ)

Explained:

- In every recession since World War II, we have seen a combination of contracting output (GDP) and rising unemployment. Yet, today we face the prospect of a recession with an extremely tight labor market. This means that a lot of Americans are employed, which is not something you’d typically associate with a bad economy. To technically qualify as a recession, output (GDP) must decline in two consecutive quarters, so we are halfway there now after the first quarter of this year. Estimates for the second quarter have been revised down as well. From the article, “the backdrop to U.S. jobs is now unusual. The U.S. has recorded more than 11 million unfilled job openings in six of the past seven months, four million more monthly openings than was typical before Covid-19 hit the economy in early 2020. In other words, demand for workers is abundant.”

What to do:

- We will find out soon whether we are indeed in a recession. So long as the labor market remains strong and mass layoffs can be avoided, it’s unlikely that the recession will be severe, and for many, life will continue unchanged whether we are in a recession or not. For investors, expect more downside in equity markets and a rally in Treasury bonds should it be confirmed that we are in a recession. That said, for much of the past two years, bad news has actually been good news for equities, as bad news increases the likelihood of favorable interventions from the Federal Reserve, so our guess is as good as yours. Regardless, you’re not alone if you think things seem a bit ‘weird’ right now.

🚨 Yield curve inverts, flashing recession warning (CNBC)

Explained:

- With regard to our explanation above discussing whether we are indeed in a recession, yield curve inversion may be a sign that investors think we are, and it’s also not the first time it’s inverted this year. The yield curve refers to a line that plots the various U.S. government Treasury bond yields (interest rates) based on their time to maturity (3-month, 2-year, 10-year, 30-year etc.) Normally, bonds with a longer time to maturity also have a greater yield, as investors demand a higher premium for locking up their money longer waiting for the bond to mature, that is, pay back its principal. The difference in interest rates for these bonds is called a spread, and when the spread between 2-year and 10-year Treasury bonds goes negative, some have seen this as a historical indicator that all is not well in the economy. In other words, shorter duration Treasury bonds holding a higher interest rate than longer Treasury bonds may predict a recession.

What to do:

- In today’s environment, this is likely because the Federal Reserve is raising overnight interest rates in response to high levels of inflation, so bonds like the 2-year Treasury have a greater premium for inflation baked into their yields while accounting for rising rate expectations from the Federal Reserve, whereas more long-term bonds like the 10-year Treasury are less sensitive to what the Fed is doing and more reliant on economic growth expectations. In other words, as the Fed hikes short-term interest rates, 2-year Treasury yields are rising in response, while 10-year Treasuries are going lower or holding steady. While many of us may be excited to see our bank accounts finally yielding more meaningful interest payments, due to higher short-term interest rates, the picture for financial markets generally is a lot less optimistic.

Sponsored By

How do you make sure that you are investing with a “good” operator?

Dan Handford and his wife are currently invested in 54 different passive real estate syndications with 16 different operators in 10,000+ doors.

They use this exact list when deciding whether or not to invest with a particular group. Get access to the “7 Red Flags for Passive Real Estate Investing” to be confident in your next investment!

Deep Dive: ‘Hyper-financialization’

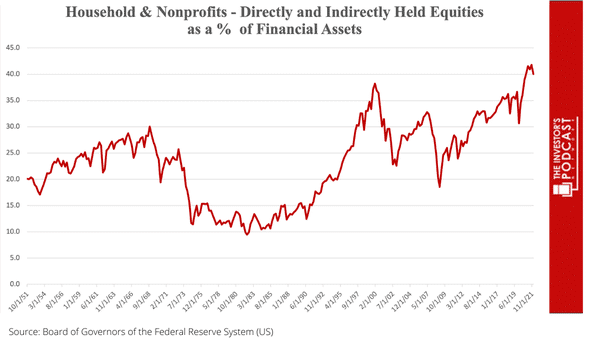

We often hear people say, “the stock market isn’t the economy,” particularly during times when the stock market is rising yet the real economy is struggling – much of 2020 comes to mind.

In theory, the stock market should generally correlate to the real economy to a certain extent, as a favorable business environment will tend to lend itself to earnings growth, which is one of the primary drivers of a stock’s price over time.

What if, though, the stock market was actually driving changes in the real economy simply through the price of equities?

This is what Julien Brigden, founder of MI2 Partners, had to say last week in an interview where he discusses what he calls “hyper-financialization.” This term is meant to describe how financial market effects artificially reverberate throughout the economy.

He explains, “company CEOs are no longer paid to produce anything…CEOs are remunerated just simply to do one thing. And they are shepherds of a stock price…the job is to tend to the stock price, drive the stock price higher.”

If we accept that many CEOs are indeed heavily driven by ensuring a high stock price, particularly since much of their compensation is often incentive-based through stock options, then there is an interesting point here to consider that there may be some reflexivity between equity prices and CEO behavior.

So what’s the issue?

As the Federal Reserve (“the Fed”) raises interest rates and puts the brake on the bull run in stocks beginning in 2020, it’s possible that corporate leaders take their signals not from the real economy, but rather from their own stock’s price, which is now likely dropping fast.

Yesterday, according to Nasdaq, 139 stocks set a new 52-week low, while just 10 set a 52-week high.

Brigden describes a feedback loop where CEOs see their stock crash, become unnerved, and then make drastic decisions, such as layoffs and spending cuts, in anticipation of a worsening economic environment.

But the point here is that this signal for action didn’t come from operating activities, rather, it came from the stock market, and more specifically, possibly the Federal Reserve.

While the Fed may or may not be aware of this dynamic, they’re certainly aware of a phenomenon known as the wealth effect. This can be seen as another example of how financial markets influence the real economy. The term refers to the idea that people spend more when they feel richer, even though much of that ‘richer’ feeling is coming from artificial investment

gains rather than more disposable income.

That is, when equity and real estate prices are rising, personal spending also increases. There’s a good argument that we saw this unfold throughout 2021, though the flip side can also be true, with financial assets rapidly losing their market value, consumers and businesses may begin to tighten their purse strings.

Many of our social institutions are reliant on continuously rising financial asset prices, particularly in equity markets. With stocks hitting a 70-year high as a share of American household wealth last year, equities become increasingly important for ensuring social cohesion, or in other words, the stock market becomes increasingly too big to fail. On this point, the stock market is perceived more as a political device than the output of a free market. No politician can afford to see equity prices drop too much without risking devastating social consequences as millions see huge swathes of their life’s savings knocked out.

While we are told that stock investing is risky, we are also told to “buy the dip,” and everyday Americans did that to a huge degree following the COVID downturn in March 2020.

Many of these new, largely Millennial and Gen Z investors, are unlikely to have ever experienced a lasting downturn in financial markets, while the belief that stocks always go up has been prevalent. Even in light of the current bear market, the possibility that stocks could underperform for years or decades is hardly mainstream, yet it remains precedented historically. It took the Dow Jones Industrial Average 25 years to return to the same level it was at before the 1929 crash. Let me say that again for emphasis, 25 years!

Perhaps you’re thinking that could never happen today. Well, that inclination is my point, many of us believe such extended harsh periods are a thing of the past — but are they? Is this time really different?

How many of us would have had a global pandemic and a war in Europe on our bingo cards the last two years though?

In more recent memory, it still took the Dow 5 years to recover its 2007 high before the financial crisis.

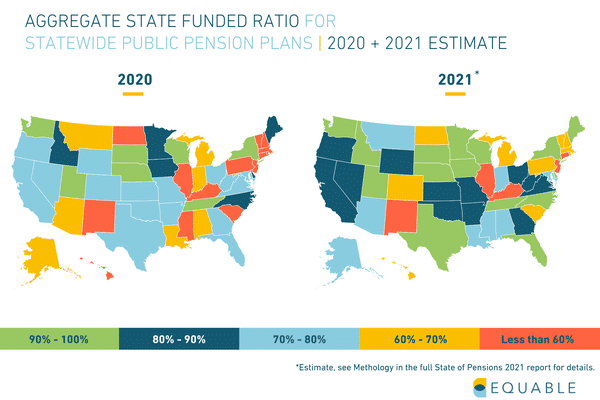

With much of Americans’ financial assets tied up in the stock market and their financial health defined by its success, let’s now consider the state of another important tool for retirement and social cohesion: pension funds.

Unfortunately, many pension funds are deeply underfunded and have turned to alternative asset classes to try and salvage the difference, in addition to a sizable reliance on public equity markets.

Pension funds, endowments, and many other large social institutions managing long-term investment capital use complex models to predict sequences of returns. Few, however, are prepared for the worst-case scenarios. In fact, some underfunded pensions must be quite optimistic about consistent high returns in equity markets to ever meet their goals.

This is all partially attributable to interest rates being so low for most of the last decade, as retail investors and institutions have had to increasingly rely on more risky approaches to compounding returns, since banks and bonds have had little to offer. On Wall Street, this is known as ‘TINA‘, an acronym meaning ‘there is no alternative’ in reference to owning stocks.

To summarize, CEOs are incentivized to respond to stock price changes, consumers respond to market movements through the wealth effect, and the underfunded pension system relies on the equity market to compensate for lackluster bond returns. We live in a world very dependent on financial asset returns, particularly from stocks.

The takeaway?

Financial markets are deeply ingrained in our collective psyche, and increasingly, they may be altering behavior in the real world, as opposed to the other way around. In an age of hyper-financialization, it’s quite important to understand the interactions between the financial system and everyday life, so we can respond to changes in either accordingly.

Quote of the Day

“I’m a shameless copycat. Everything I do in my life is cloned…I have no original ideas.”

— Mohnish Pabrai

Meaning

For those not familiar with the great value investor Mohnish Pabrai, this quote may be astonishing to hear. The takeaway is not that Mohnish has literally never had an original idea, but rather that he embraces the notion that others before us have paved the path to success, so why not simply copy their habits and strategies, instead of trying to reinvent success ourselves?

The beauty of this cloning concept is that you can extrapolate it well beyond just investing and finance, though it doesn’t hurt to study what the greats do here and mimic them as much as possible – no wonder the annual Berkshire meetings are so popular.

There’s tremendous humility in recognizing that others know better than you and a willingness to learn from them will carry you a long way.

Surely, you’ll need a few original ideas to become a successful stock picker, though if you can study and embrace the habits of investing greats, you may be one step closer to finding your own success.

To hear more from Mohnish, check out some of our recent podcast interviews with him on We Study Billionaires episode 442 and Richer, Wiser, Happier episode 8.

Behind The Jargon: Mutual Funds And ETFs

Yesterday, we discussed direct indexing as a possible future innovation in wealth management over mutual funds and ETFs. Which raises a good question – what exactly is the difference between mutual funds and ETFs anyways?

Mutual funds are companies with pools of investors’ money that have managers to choose investments and allow you to access a broad range of stocks and bonds in a single product.

An ETF is a type of pooled fund that trades like an individual stock throughout the day and tends to have fewer costs than regular mutual funds, which are often less tax-efficient and only trade at the end of the day.

ETFs are seen as more tax-efficient (according to Fidelity) because unlike mutual funds, where managers have to sell assets routinely to accommodate redemptions or rebalance the portfolio and realize capital gains, these products have fewer taxable events (selling of assets) thanks to the help of ‘authorized participants’.

These authorized participants are sophisticated financial institutions who purchase the relevant financial assets on behalf of the ETF and store them in a trust, so shares in the ETF represent claims on the trust’s assets. When investors want to redeem the ETF’s assets, they can gather a large number of shares and conduct an ‘in-kind’ transaction, which is essentially just an exchange of the ETF’s shares for the underlying assets.

On the other hand, mutual funds do not have this structure. Instead, through “the sale of securities within the mutual fund portfolio, (mutual funds) create capital gains for shareholders, even for shareholders who may have an unrealized loss on the overall mutual fund investment” (Fidelity).

What to know

ETFs have significantly disrupted the asset management world in recent years, while mutual funds’ advantages stem from being around longer, so there’s a wider variety of mutual fund strategies and greater active management.

Mutual funds also offer more investor services but may have sizable minimum investments and greater embedded fees.

Increasingly, mutual funds struggle to compete with ETFs and for good reason, so for most readers, ETFs will prove more accessible, affordable, and understandable.

To learn more, check out our course on How To Invest in ETFs by Stig Brodersen.

See You Next Time!

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

If you enjoyed the newsletter, keep an eye on your inbox for them on weekdays around 12 pm EST, and if you have any feedback or topics you’d like us to discuss, simply respond to this email.

Have a great rest of your day!

P.S The Investor’s Podcast Network is excited to launch a subreddit devoted to our fans in discussing financial markets, stock picks, questions for our hosts, and much more! Join our subreddit r/TheInvestorsPodcast today!