Reality Check

30 January 2023

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

It’s happening again — for five straight weeks, gas prices have been rising, reaching an average of $3.49 per gallon in the U.S. Fortunately, we’re still 30% off from last summer’s peak ⛽

In markets, mean reversion has gotten some major validation thus far in 2023, as 50 of last year’s worst S&P 500 stocks are up this year, on average notching gains of 20%.

More than 100 companies representing a third of the S&P 500’s market value will report earnings results this week, including Pfizer, McDonald’s, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, and Starbucks.

👊 Of the 29% of S&P 500 companies that reported already, 69% have topped analyst earnings estimates, with aggregate earnings coming in about 1.5% above expectations, according to Factset.

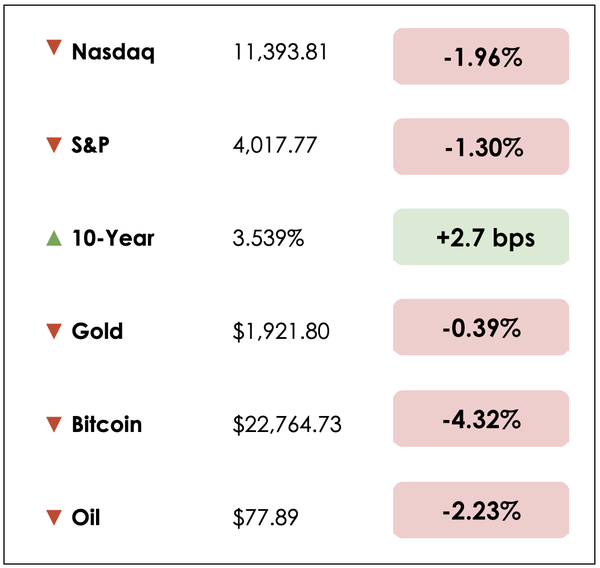

Stocks were a bit anxious still:

MARKETS

*All prices as of market close at 4pm EST

Today, we’ll discuss two items in the news: the ethically dubious story of how one drug company made $114 billion, and an update on the used car market, plus our main story on how America’s heartlands may offer an alternative to owning bonds.

All this, and more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Get smarter about valuing businesses in just a few minutes each week.

Get the weekly email that makes understanding intrinsic value

easy and enjoyable, for free.

IN THE NEWS

- Biopharma company AbbVie (ABBV) has made about $114 billion on a blockbuster drug called Humira, an anti-inflammatory medication used to treat conditions like arthritis.

- Through its savvy but legal exploitation of the U.S. patent system, Humira’s manufacturer, AbbVie, blocked competitors from entering the market. For the past six years, the drug’s price kept rising as it captured the entire market. Today, Humira is the most lucrative franchise in pharmaceutical history.

- This underscores how some pharma companies delay competition and artificially prop up prices on their best-selling drugs. Over the past 20 years, AbbVie and its former parent company raised Humira’s price about 30 times, most recently by 8% this month. Since 2016, the drug’s list price has gone up 60% to over $80,000 a year.

- AbbVie isn’t the first to deploy a patent-prolonging strategy; Bristol Myers Squibb (BMY) and AstraZeneca (AZN) have used similar tactics to maximize profits on drugs for the treatment of cancer, anxiety, and heartburn. The industry is ripe with companies manipulating the U.S. intellectual-property regime.

- Patents are good for 20 years after an application is filed. They’re supposed to incentivize the expensive risk-taking that occasionally yields breakthrough innovations. But drug companies have periodically turned patents into weapons to thwart competition.

- In short, AbbVie has been aggressive about suing rivals that try to introduce similar drugs. But the party is likely over, as Amgen’s (AMGN) Amjevita will come to the market in the U.S. next week. Up to nine more competitions will follow suit this year from pharma giants such as Pfizer (PFE). Prices are expected to tumble, making the drug more affordable and ending AbbVie’s monopoly.

- The pandemic used-car boom is coming to an abrupt end as dealerships see sales and prices drop, mainly because consumers are tightening their spending during a high-inflation, high-interest-rate environment.

- In 2021, the used-car business was on a tear thanks to the pandemic’s low-interest rates and stimulus, plus a global semiconductor shortage that forced automakers to stop or slow production of new cars and trucks. This pushed consumers to used-car lots, and prices for pre-owned vehicles surged.

- But Americans are on tighter budgets and buying fewer cars as interest rates rise and fears of a recession grow. Improved auto production has eased the shortage of new vehicles. Some estimates say used-car values fell 14% in 2022 and are expected to fall another 4% this year, a shift causing many dealers to sell some vehicles for less than they paid.

- Carvana (CVNA) exemplifies the industry-wide challenges. The company, which sells cars online and became famous for building “vending machine” towers where cars can be picked up, reported a quarterly loss of more than $500 million and has laid off 4,000 employees. Its stock has fallen by nearly 95% in the past 12 months.

- The used-car business is made up of thousands of small outlets, many of them family businesses. The average interest rate on used cars is around 12%, up from less than 10% a year ago, according to Cox Automotive.

- “After a huge run-up in 2021, last year was a reality check,” said Chris Frey, senior manager of economic and industry insights at Cox, a market research firm. “The used market now faces a challenging year as demand weakens.”

The Green Coffee Company (GCC), a Legacy Group portfolio company and Colombia’s #1 largest coffee producer, has launched its $100 million Series C funding round.

Earn an 11x multiple on investment projected through a 2026 sale or U.S. IPO:

WHAT ELSE WE’RE INTO

📺 WATCH: Want to watch a weekly recap of this newsletter? Check out last week’s roundup

👂 LISTEN: The Education of a Value Investor, with Clay Finck

📖 READ: 11 tech trends to watch in 2023 & a vast Maya kingdom was discovered in Guatemalan jungles

“I’d rather own all the farmland in the U.S. than all the gold in the world“

— Warren Buffett

Farmland isn’t the first place investors look to when trying to maximize returns or diversify their portfolios.

Still, with billionaires like Bill Gates snapping up hundreds of thousands of acres, there must be a good reason for interest in this multi-trillion-dollar asset class.

For Carter Malloy, the CEO of AcreTrader, there’s a lot to love about farming. In a past interview with Stig Brodersen, Malloy gives the full rundown.

Breaking it down

He says, “one of the reasons that (farmland) has always been attractive, I believe will remain so, is that it can serve as a hedge against inflation.”

See, it produces one of the core components of inflation statistics: food. He argues that farmland historically has rivaled gold as an inflation hedge, with the bonus of producing income.

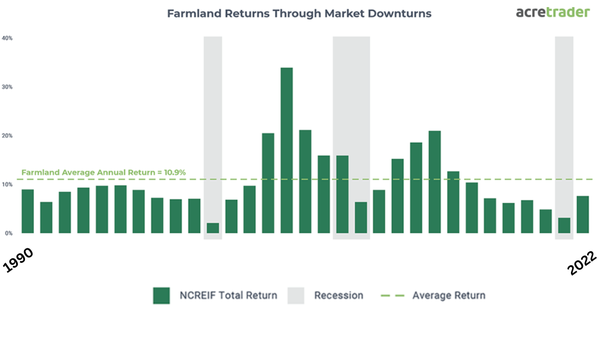

He explains that “(farmland) has put up some really great risk-adjusted returns, low double-digit types of returns, with low volatility as well.”

The thesis

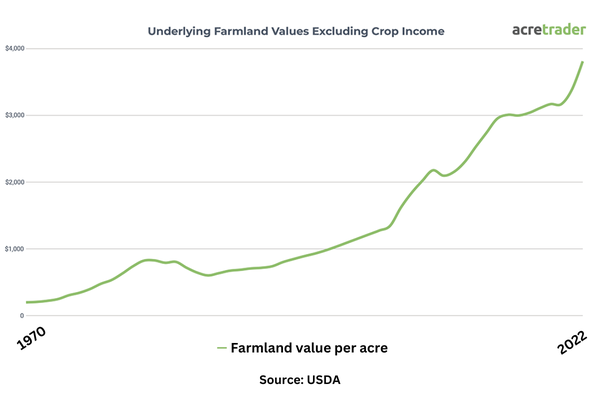

According to the non-profit Farmland Trust, the U.S. loses about three acres of farmland every minute due to development. In other words, the supply of farmland is often decreasing, yet demand is growing as we have more and more people to feed.

Of course, improved productivity in farming has enabled this shift, as we can generate more food with less land. And new technologies will almost certainly continue optimizing production in the future, yet these improvements may be less dramatic than in earlier periods of the industrial revolution.

The world’s food supply remains incredibly fragile given the planet’s growing population, evidenced by many of the disruptions we’ve seen over the last year, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one of the world’s largest wheat and fertilizer producers.

As an asset class, the thesis generally is logical: the supply of farmland is decreasing while demand for food is increasing, and productivity improvements are unlikely to fully offset that difference.

Therefore, the farming operations and their underlying properties are expected to become more valuable from rising food prices and demand for land development, respectively.

The picture is, naturally, more nuanced, with variations by region in land quality, crop types, environmental regulations, etc.

How do we get paid as farmland investors?

Mallow highlights that about 40% of U.S. agricultural lands are absentee-owned, meaning it’s not the farmers who own them.

The landowner charges farmers rent as a landlord would in an apartment building, but the farmers typically make these payments semi-annually or annually. Unlike apartment rentals, this industry sees much lower vacancy and default rates.

Investors receive cash flows from rental payments while also benefiting from increases in land value. These land value increases can stem from real estate prices rising broadly or from food prices rising and making that land’s output more valuable.

Permanent versus row crops

This description fits the majority of American farmland, which utilizes row crops.

Within the farmland asset class, there’s a possibility for diversification with lands devoted to permanent crops, too. These crops grow on vines, bushes, or trees, like apples, oranges, olives, and almonds, as opposed to row crops like corn or soy.

In permanent crop investments, the investor usually owns both the underlying land and the trees, which adds more direct exposure to commodity prices. For example, in owning almond trees, your profits would be tied to swings in almond prices.

Consequently, returns tend to fluctuate more for investors in permanent crops.

Tradeoffs

Malloy details further that in row crop investing, due to its more standardized outputs, cash flows from crops tend to fuel returns less than land prices because the land may have more flexible uses and can appreciate faster if it’s a quality parcel than permanent crop properties.

With permanent crops, because the land is devoted to more specialized purposes, land price increases tend to be modest, especially considering that the value of your assets on that land (i.e., grape vines, olive trees, etc.) naturally depreciate after they hit the peak production points in their lifecycle.

However, prices for permanent crops tend to have more upside, meaning they produce better cash flows over time.

Takeaways

So the return profiles can be quite different for row crop or permanent crop investments, where one (row) drives most of its returns from land appreciation and the other (permanent) earns most of its returns from commodity price appreciation.

While the asset class hasn’t seen a down year since 1990, according to Malloy, it’s not the kind of bet to make you rich quickly.

He says further, “You’re not going to go buy a piece of farmland and turn it around the next year and sell it for double…it’s all about compounding over time, call it an old school Buffett mentality of buying quality assets that are simple and allowing your money to work for you.”

Farmland investing represents a formidable long-term store of value with reasonable return prospects backed by real, physical assets, as opposed to paper IOUs from governments with historically low inflation-adjusted yields via bonds (even with the rise in interest rates in the past year).

Dive deeper

To zoom in on specific investment opportunities in the farmland space, AcreTrader is an excellent resource.

And to hear Carter Malloy’s full interview on farmland investing, you can listen to it here.

*For full transparency, AcreTrader has been a sponsor for our podcasts and newsletter periodically, but this is an unpaid write-up. Like most of you, we’re also learning about farmland investing, and AcreTrader is a leader in this space.

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

See you later!

If you enjoyed the newsletter, keep an eye on your inbox for them on weekdays around 6pm EST, and if you have any feedback or topics you’d like us to discuss, simply respond to this email.