How to Decide

19 February 2023

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

Get smarter about valuing businesses in just a few minutes each week.

Get the weekly email that makes understanding intrinsic value

easy and enjoyable, for free.

Simple setup for new Bitcoiners ✅

Advanced features for Bitcoin veterans ✅

The Bitcoin wallet for your every need ✅

Blockstream Jade is the only hardware wallet designed for your whole Bitcoin journey. Visit store.blockstream.com and use coupon code: ‘Fundamentals’ to get 10% off your Blockstream Jade.

A major Super Bowl decision

One of the most controversial decisions in Super Bowl history occurred in the closing seconds of Super Bowl XLIX in 2015. With 26 seconds left and down four, the Seattle Seahawks had the ball on second down at the New England Patriots’ one-yard line.

Most expected Seahawks coach Pete Carroll to call for a handoff to running back Marshawn Lynch, one of the best running backs in the NFL.

But Carroll called for quarterback Russell Wilson to pass, and New England intercepted the ball, winning the Super Bowl.

The Washington Post called the decision “the worst play-call in Super Bowl history.”

Yet all the Monday Morning quarterbacks missed something hidden in plain sight: The decision to throw the ball was sound, if not brilliant. An interception was a doubtful outcome.

Out of 62 passes attempted from an opponent’s one-yard line during the season, zero had been intercepted. In the previous 15 seasons, the interception rate in that situation? 2%.

Many people blamed Carroll for the loss, but he made a sound decision based on the information available. He just got unlucky.

Resulting

Carroll was the victim of our tendency to equate a decision’s quality with its outcome, according to Annie Duke, a former professional poker player turned cognitive-behavioral decision science writer and educator.

A good outcome might be the result of a bad decision, and a bad outcome can be the result of a good decision. Don’t confuse the outcome with the quality of the decision. That’s called “resulting.”

Results overshadow the decision process, leading you to overlook important information.

You can see how this could relate to investing, where you can make a sound decision and still lose money. Or, we can make a poor decision but generate the desired return due to luck.

Avoiding our tendency to analyze our own investment decisions solely based on outcomes, rather than the actual decision process, is critical to improving the quality of our decisions.

Studying our choices can help us be better investors.

Getting comfortable with uncertainty

Imagine your best investment decision in the past year or two, as well as your worst.

Chances are, your best decision preceded a good result, and your worst decision preceded a bad result.

Writes Duke: “When you make a decision, it’s rarely guaranteed to get a desired outcome (even if that’s a good decision). Your goal then should be to choose the option that will lead to the most favorable ‘range of outcomes’.”

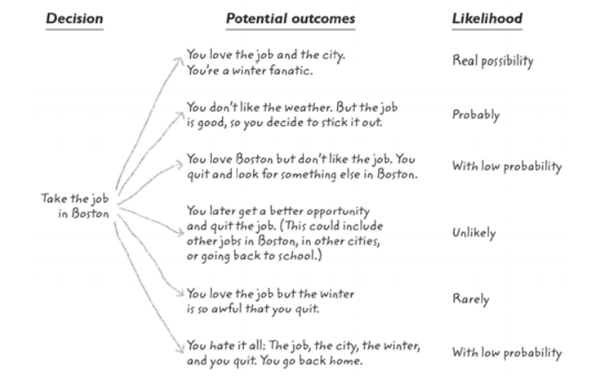

Before making a decision, Duke suggests starting with a decision tree to document potential decisions, possible outcomes, and the likelihood the outcomes will occur.

The latter is the most important and overlooked. It’s about probabilities:

Unparalleled star power

Some of Duke’s mental models for decision-making:

- Identify the reasonable set of possible outcomes. Create a decision tree. Examine a decision by asking yourself: What facts do I have? What do I know and what do I believe? What assumptions or biases might be hiding in those beliefs?

- Identify your preference for each outcome. List the potential outcomes on your decision tree in order of your most preferred to least preferred. For nearly every decision, there are outcomes we hope for and others we don’t. You need to think about whether a potential outcome is good or bad, but also how good or bad.

- Think outside of a particular decision. You might say to yourself, “What are the kinds of factors that would help someone in my shoes come to a sound decision here?”

- Bring others in and listen. But when asking others for feedback on a decision, don’t tell them what you think before you find out what they believe.

- Review the good with the bad. “Examining only one side of the equation not only causes you to miss out on half of your opportunities to learn, but it also encourages people to be too conservative in their projections,” Duke writes.

Other tips from Duke

Trim the number of decisions you make to try to increase the quality of the decisions you do make. Some elite investors set a limit to the number of stocks they own or buy/sell in a given year to ensure they’re making fewer but higher-quality decisions.

“Trust your gut” is standard advice, but Duke warns that the “gut” is where our biases live. It’s not necessarily your best decision-making tool, and it can be emotionally wired.

More people involved in a decision is helpful, assuming you leverage each person’s independent thinking rather than simply urge them to confirm your belief.

Break free from analysis paralysis. The average person spends about 250 hours per year deciding what to eat, watch on TV and wear. Thus, we need systems to organize and streamline small, routine decisions. Sometimes, less information is an advantage.

Final word

To be a better thinker and investor, consider the role of resulting and hindsight bias. Consider starting an investing journal to jot down and internalize your decisions, then revisit past decisions to review your thinking and where you went right or wrong.

Try utilizing a decision tree before your next investment. Duke recommends avoiding a pro/con list in decision-making, as it reinforces biases you already have.

Tell us, readers: What works for you when making tough decisions?

Dive deeper

Catch Duke’s fascinating interview with William Green here.