Contagion Continues

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

🚨 A pandemic, war in Europe, and bank runs — it’s unsettling to live through these historic events, yet here we are.

After three banks failed in five days, with rumors of more to come this week, government officials worked through the weekend to stave off a broader bank run Monday morning.

Their plan, announced Sunday night, guarantees all deposits will be honored with help from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which will raise funds from levies on licensed banks across the country.

It’s not a taxpayer-funded bailout per se, but let the political games of defining a bailout begin 💭

Regardless, smaller banks across the U.S. got crushed today on fears of continued bank runs. The regional banking ETF, KRE, suffered double-digit losses. Bitcoin seemingly took delight in the banking chaos, though, jumping over 13%.

Here’s the market rundown:

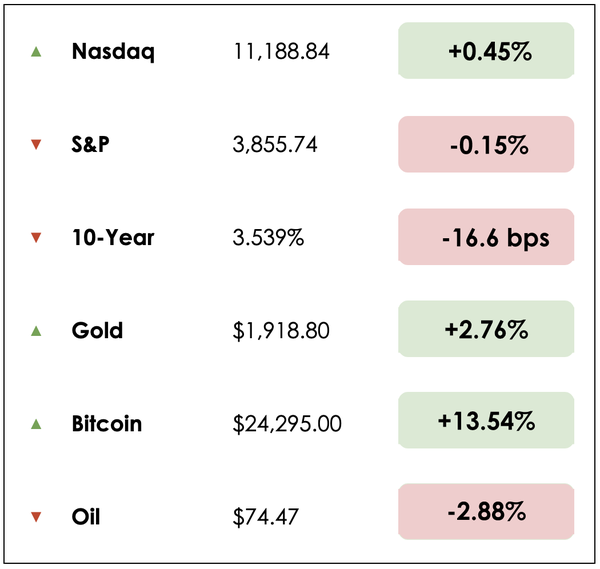

MARKETS

*All prices as of market close at 4pm EST

Today, we’ll discuss two items in the news:

- President Biden’s efforts to restore faith in the banking system

- A historic bond rally spurred by the banking crisis

- Plus, our main story on what would really happen if the U.S. government defaults on its debt

All this, and more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Understand the financial markets

in just a few minutes.

Get the daily email that makes understanding the financial markets

easy and enjoyable, for free.

Real estate investing, made simple.

17% historical returns*

Minimums as low as $5k.

EquityMultiple helps investors easily diversify beyond stocks and bonds, and build wealth through streamlined CRE investing.

*Past performance doesn’t guarantee future results. Visit equitymultiple.com for full disclosures

IN THE NEWS

💵 Biden Offers Assurance (NYT)

Explained:

- President Joe Biden said Monday morning that banks need more regulatory oversight after the closure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) on Friday and then Signature Bank on Sunday.

- Many large and regional bank stocks tumbled Monday as regulators tried to contain the damage from SVB’s collapse. But Biden said: “Every American should feel confident that their deposits will be there, if and when they need. Second, the management of these banks will be fired.”

- Investors and banks will not be protected, according to Biden. “They knowingly took a risk,” he said. “When the risk didn’t pay off, investors lose the money. That’s how capitalism works.”

Why it matters:

- There are “important questions” about how SVB and Signature found themselves in this position, the president said — problems his administration has signaled they’re working on addressing.

- Among the stocks halted at one point on Monday: Charles Schwab, one of the most mainstream names in banking. In 2020, Schwab acquired TD Ameritrade, and held about $800 billion in deposits and hundreds of billions of dollars in other funds, according to its latest annual report.

- The Federal Reserve announced it would set up an emergency lending program, with approval from the Treasury, to funnel funding to eligible banks and help ensure they can “meet the needs of all their depositors.” Notably, this includes lending against government securities at par value, helping banks avoid realizing losses inflicted by over a year of rate hikes.

📈 Historic Bond Rally (WSJ)

Explained:

- Turmoil in the banking sector sparked a rally in government bonds Monday, with yields on some shorter-term Treasuries collapsing half a percentage point in hours.

- Yields, which fall when bond prices rise, started falling during the Asia trading session soon after U.S. regulators, including the Federal Reserve, announced measures on Sunday night intended to mute the fallout from Silicon Valley Bank’s sudden collapse on Friday.

- The plunge underscores how quickly investors have pivoted from worrying about inflation and interest rate increases to focusing on how problems with banks could damage the economy.

Why it matters:

- On Wednesday, investors had wagered there was a nearly 80% chance that the Fed would lift rates by 0.5 percentage points at its coming meeting. Just a few days later, that seems unfathomable to some, only adding pain to a financial system that the government is trying to protect from contagion.

- On Tuesday, the Labor Department will release its latest consumer-price index report, providing the first look at how inflation developed in February after data showed prices rose unexpectedly quickly in January. A hot inflation report would complicate things further, as the Fed seeks to reconcile its fight against inflation with preserving financial stability.

- The yield on the two-year Treasury note last week topped 5% for the first time since 2007. Early Monday, it was trading at 4.074%, on course for its biggest one-day decline since 2008. The yield has fallen faster than in any three-session stretch since 1987.

High stakes politics

Everyone’s talking about regional bank defaults, but what if the U.S. government itself defaults?

If you’ve been under a rock — one of today’s biggest political issues is that a divided Congress may have difficulty raising the debt ceiling to fund the federal government over the coming months.

We’ve actually already bumped up against this debt issuance limit, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has suggested that we have until around June before the government runs out of cash to pay its bills, raising the possibility of default for the government of the world’s largest economy.

In 2011, S&P downgraded the United States’ credit rating in response to a similar budget crisis, but financial markets globally have typically dismissed default worries as political theater.

A default that hindered trust in American institutions would surely be catastrophic, right?

Nonsensical laws

George Pearkes, a macro strategist at Bespoke Investment Group, calls the crisis “nonsensical.”

That’s because we have a system of checks and balances where Congress is democratically elected. Then it works through tedious internal processes to authorize government spending, which is signed into law by the President.

Yet, unlike most democratic countries, we have an extra layer of constraint. Spending is authorized by Congress and the President but may not necessarily be appropriated funds for implementation due to the debt ceiling.

Pearkes emphasizes that the debt ceiling, though, is an arbitrary line in the sand. Any default on the government’s bills from this crisis would be a self-inflicted wound.

Digging our own grave

In other words, the government has made a legal plan to fund itself, and free markets aren’t the ones denying the U.S. government the necessary funding in capital markets. Instead, Congress is artificially imposing a constraint that risks a global financial crisis.

He argues that rather than adding value as a reason to publicly debate government spending every few years, the debt ceiling has more often been used by “one faction or another in U.S. politics against whoever happens to be the party in control.”

It’s become a political weapon used by the minority party to obstruct the majority at considerable financial risk. The costs so wildly exceed the pros of having a ceiling that this political game is, in a word, reckless, at least according to Pearkes.

What would a default look like

The Treasury is taking “extraordinary measures” to stave off default until the ceiling is raised. The Treasury has the equivalent of a checking account at the Federal Reserve, and it’s draining that balance down, only to be replenished by new tax inflows or new debt issuance, which is mostly on pause.

One popular proposal is to consider spending prioritization. If cash gets tight, the Treasury would prioritize payments on the most urgent debts, such as interest payments on bonds, instead of contributions to government workers’ retirement accounts which could be delayed in an emergency.

Pearkes explains that this is a difficult and ultimately extremely political question to decide who gets paid and who doesn’t. The unelected bureaucrats working in the Treasury Department aren’t qualified or interested in assuming that responsibility.

Y2K?

If a payment is missed, that’s when things get interesting, and there may be technical factors that throw markets into chaos.

For example, it’s unclear whether the operating systems at banks can even register and settle transactions with Treasury bonds beyond their maturity date.

It would be like a Y2K event, where most banks never programmed into their systems what to do with Treasuries that are still outstanding past the payback date, because no one ever expected the government to miss its debt payments.

Still, Pearkes thinks that as long as there’s reason to believe the debt limit could be resolved soon after an initial default, most investors would probably be willing to buy Treasuries at a slight discount to earn an extra profit when the government is operating normally again.

So the total collapse of financial markets in a default isn’t necessarily guaranteed.

Averting crisis

It’s a gray area, but section four of the 14th amendment came after the civil war to ensure that legally authorized federal spending couldn’t be hindered by Southern politicians protesting reconstruction measures.

Pearkes says, “there’s a general constitutional principle that if the United States government owes someone something, you can’t get in the way…That’s the plain text reading of that.”

Rather than offering a solution to the immediate possibility of default, the invocation of the 14th amendment by the President would probably kick off a lengthy legal debate over whether the debt ceiling is constitutional.

Another emergency measure includes the issuance of bonds at significantly above-market rates. The Treasury could try to supply itself with funding by issuing bonds with coupon rates an order of magnitude higher than the yields offered by normal Treasury bonds.

Consider, for example, a 30-year bond with a coupon rate of 100%, compared to the regular 30-year bonds currently offering around 4%. Investors would likely massively bid up prices on bonds with hefty coupon payments in a Treasury auction.

So a bond with a principal amount of $100, with a super high coupon rate, may actually sell for $1,800. Selling billions of dollars worth of these securities (up until the limits of the debt ceiling) would provide a huge short-term injection of cash into the Treasury, with the trade-off of unprecedented interest payments (which aren’t counted towards the debt ceiling).

It’s not a financially sound move, but it could technically avert a crisis.

Let’s hope we don’t have to find out the answers to any of these questions.

Dive deeper

Check out Pearkes’ interview on Bloomberg for more.

SEE YOU NEXT TIME!

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.