Buffett’s Berkshire

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

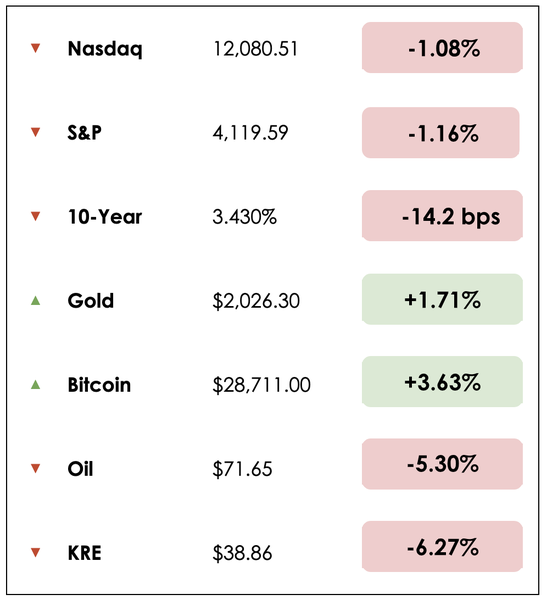

Ugly day for stocks. With the Fed’s next interest rate hike decision coming tomorrow, it was hoping to see a better reaction to JPMorgan’s acquisition of First Republic 🤞

But investors are still jittery about regional banks. PacWest’s stock fell more than 27%, Western Alliance dropped over 15%, and the Bank of Hawaii stumbled almot 8%.

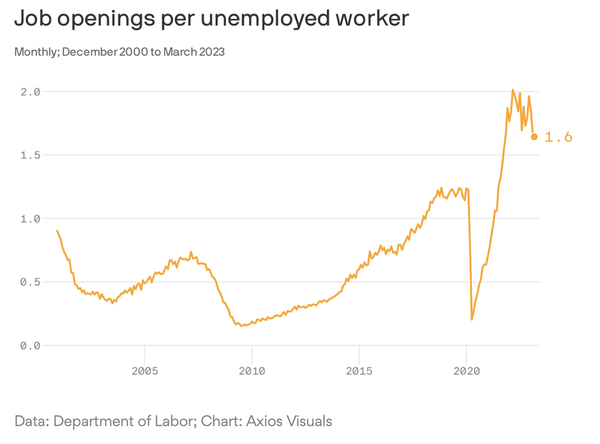

🌤️ On the bright side for the Fed, which hopes a weaker economy will bring down inflation, the job market continues to cool off.

Job openings declined for the third straight month in March, decreasing by 384,000, while the quit rate declined — suggesting people feel less confident they can leave their job and find another one.

Still, there are 1.6 open jobs for every unemployed worker (see our Chart of the Day for this visualized).

—Shawn

Here’s the rundown, featuring the S&P Regional Banking ETF (ticker: KRE):

MARKETS

*All prices as of market close at 4pm EST

Today, we’ll discuss two items in the news:

- Warnings about A.I.

- Why inflation is so sticky

- Plus, we continue with day 2 of Berkshire Week, with our main story on how Warren Buffett took over Berkshire Hathaway

All this, and more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Today’s trivia: Since Buffett took control of Berkshire Hathaway in 1965, what’s the stock’s average annual rate of return through 2022?

(Scroll to the end to find out).

Get smarter about valuing businesses in just a few minutes each week.

Get the weekly email that makes understanding intrinsic value

easy and enjoyable, for free.

IN THE NEWS

❗A.I. Pioneer’s Warning (NYT)

Artificial intelligence pioneer Geoffrey Hinton has left Google after more than a decade at the search giant, citing fears about the rapid development of generative A.I.

- Hinton is widely viewed as the godfather of modern artificial intelligence but said he quit his powerful (and lucrative) job to speak freely about the dangers of A.I.

- The 75-year-old British scientist told The New York Times that he partly regretted his life’s work, as he warned about misinformation flooding the public sphere and A.I. usurping more human jobs than predicted.

“I console myself with the normal excuse: if I hadn’t done it, somebody else would have.” He added that it was “hard to see how you can prevent the bad actors from using it for bad things.”

The A.I. race: Hinton said he was concerned the race between Google and Microsoft to launch AI-driven products would push forward the development of A.I. without appropriate guardrails and regulations in place.

Why it matters:

To be clear, A.I. has enormous positive potential for everything from replacing strenuous, monotonous tasks to spotting cancer early. Still, Hinton sees the potential for enormous downside risk.

- As companies improve their A.I. systems, he believes, they become increasingly dangerous. “Look at how it was five years ago and how it is now. Take the difference and propagate it forward. That’s scary.”

- And now that Microsoft has augmented its Bing search engine with a chatbot — challenging Google’s core business — Google is racing to deploy the same kind of technology. The tech giants are locked in a competition that might be difficult to stop.

His immediate concern is that the internet will be full of false photos, videos, and text, and the average person will “not be able to know what is true anymore.” He also fears a day when truly autonomous weapons — killer robots — become a reality.

Possible solution: He says the best action is for the world’s leading scientists to collaborate on controlling the technology. “I don’t think they should scale this up more until they have understood whether they can control it.”

💵 Why Is Inflation So Sticky? (WSJ)

U.S. inflation eased in March to its lowest level in nearly two years, a positive development for many American families. But it has still proved sticky as families feel squeezed at the grocery store and when paying their rent or mortgage.

Justified? Companies have continued raising prices after the supply-chain disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and the energy, food, and raw-material bottlenecks that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have pushed costs higher.

- However, there are signs that companies are doing more than simply covering their costs.

Why it matters:

Economists say businesses have been padding their profits, which fueled inflation during the second half of last year.

- Sometimes, widespread knowledge of rising costs allows businesses to raise their prices, knowing that their competitors will act similarly.

Interestingly, much of the surge in food prices since the middle of last year stems from higher costs, particularly for energy, since most food production is energy-intensive. But economists have calculated that about 10% of the rise reflects the search for higher profits.

- They suggest that’s possible because, “There’s not enough competition in the food sector, especially in distribution,” said Ludovic Subran, chief economist at Allianz.

Relief could be coming: In recent earnings calls, some executives said consumers were becoming more resistant to price rises. And Proctor & Gamble warned that there were limits to how far it could push raise prices before consumers switched to cheaper alternatives.

MORE HEADLINES

🇺🇦 Russia fears Ukraine could achieve ‘major breakthrough‘

💼 Chegg stock drops 40% after saying ChatGPT is killing its business

📉 Scathing report from short seller sends Carl Icahn’s company down 24%

A man and his company

Today, Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway are synonymous. Buffett, to many, isn’t just the physical manifestation of Berkshire but of American Capitalism itself.

Did you know, though, that Berkshire Hathaway existed long before Buffett?

The iconic company traces back to two Massachusetts cotton mills, Berkshire Fine Spinning Associates and Hathaway Manufacturing, which merged in 1955 to form Berkshire Hathaway. The new company was a formidable force in textiles, employing 12,000 workers and earning over $120 million in annual revenue.

A dying industry

That is, until the end of the decade, when the American textile industry collapsed, with much of its jobs outsourced to lower-wage workers elsewhere. Berkshire Hathaway saw seven of its 15 New England plants close. The company was in dire straits.

The company caught Buffett’s attention in 1962, true to his mentor Benjamin Graham’s signature “cigar butt” approach to investing, looking to squeeze the last puffs of value out of a stock as you might with a cigar.

Each time a textile mill was closed, Buffett noticed Berkshire’s stock actually went up. That’s because, as Buffett has since explained, “Berkshire Hathaway was closing mills, and as they closed mills, it would free up some capital, and then they would re-purchase shares.”

Taking a stake

Buffett started buying up shares around $7.60 a piece, which he believed were worth at least $19 per share considering the net asset value on its books. By 1965, he had a roughly $14 million stake.

At the time, he managed investments through Buffett Partnership, Ltd. Starting with $105,000 in 1956 at the age of 25, he used a blend of his own money and funds raised from his mother, sister, aunt, father-in-law, brother-in-law, college roommate, and lawyer.

Early investing successes made Buffett a millionaire, but there are plenty of millionaire stock investors that you’ve never heard of before.

His legendary story centers around building Berkshire Hathaway. If necessary, Buffett figured the dying company could be shut down and liquidated to realize the difference between the discounted share price and the cash value of those assets.

But Seabury Stanton, Berkshire’s then-chairman and CEO, reached out to Buffett about buying back his partnership’s stake.

Realizing he could secure a decent profit without having to wait for the company’s intrinsic value to be fully realized, Buffett verbally agreed with Stanton to submit a tender offer, proposing to sell his shares in the company at $11.50 a piece.

Buffett gets emotional

Had the company simply accepted his offer, Buffet would’ve sold out of Berkshire, and who knows whether we’d even know his name today. Instead, Buffett received a note offering to buy his holdings at $11.375 per share, 1/8 of a dollar less than their agreed price.

That was an infuriating response to his good faith offer, prompting Buffett to retaliate by buying as many shares in the company as he could to boost his influence over management.

In a 2010 interview, Buffett remarked, “He chiseled me for an eighth. And if that letter had come through with 11 and a half, I would have tendered my stock. But this made me mad. So I went out and started buying the stock, and I bought control of the company and fired Mr. Stanton.”

In that same interview, he admits that despite the later successes, buying Berkshire out of spite was one of his dumbest investments ever.

Turning the ship around

Buffett knew the American textile industry was in terminal decline, and as a controlling shareholder, he looked to make the most of the situation.

The transition from textile company to mega-conglomerate was slow, but the first major pivot occurred in 1967 when Berkshire acquired National Indemnity, an insurance company, for $8.6 million.

Buffett would later say without that deal, Berkshire “would be lucky to be worth half of what it is today.”

Buffett wound down his partnership in 1969 and went “all in on Berkshire,” according to Adam Mead, author of The Complete Financial History of Berkshire Hathaway. Next, Berkshire bought Illinois National Bank in a large deal that was worth 44% of Berkshire’s equity capital.

Mead adds, “Those first two big acquisitions are really the start of reallocating capital from a dying textile business into something better.”

Final thoughts

Buffett commandeered a narrowly-focused textile company in Berkshire and used it to build one of America’s most sprawling and famous corporate empires.

Twenty years after taking over Berkshire, he closed down all textile operations, replacing it over the years with majority ownership in many brands you likely know well, such as Benjamin Moore, GEICO, Dairy Queen, Duracell, See’s Candies, and minority stakes in companies like American Express, Apple, Bank of America, Chevron, Coca-Cola, General Motors, Kraft Heinz, and many, many, more.

Dive deeper

To learn more about Buffett’s early days and how he became the best investor of all time, check out this We Study Billionaires podcast episode.

TRIVIA ANSWER

From 1965 through 2022 Berkshire Hathaway’s stock has compounded at approximately 19.8%, compared to 9.9% (including reinvested dividends) for the S&P 500.

SEE YOU NEXT TIME!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.